- Home

- Cooper-Posey, Tracy

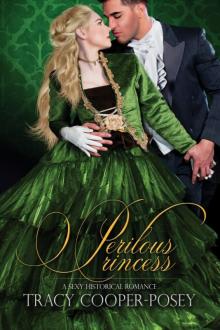

Perilous Princess: A Sexy Historical Romance Page 2

Perilous Princess: A Sexy Historical Romance Read online

Page 2

Natasha nodded, watching the poor girl under discussion sip her glass of punch, her glove already stained with the juice. Sarah was unfashionably thin and her dress was two years old and unflattering. It was rumored her father’s fortune no longer existed.

“The one with the orange hair?” Rhys asked.

“Indeed. Or the lady over by the port gunwale, with the lavender dress.”

“Lady Mary is to be officially engaged to the Earl of Wickley after Easter,” Natasha pointed out.

“Who is that very unattractive one over there by the mast?” Rhys asked. “Is she…? I do believe she is actually reading a book.”

Natasha looked. The woman he was referring to wore a plain blue dress. The fabric was silk and the color glowed, however, there was little adornment about her to enhance the effect. Her hair had been pulled up tightly upon the crown of her head, when everyone else parted their front hair and braided or coiled or wound the lengths into ringlets, while the fashion in back hair styles was even more elaborate. The woman’s hair was, Natasha suspected, a golden color that the blue silk of her dress would complement nicely, but because it was so tightly wound into the hard little bun, it was difficult to appreciate the color at all. Laid flat and tortured in that way, the gold was faded and uninteresting.

She was indeed reading a book and she sat quite alone.

“That is Princess Annalies of Saxe-Coburg-Weiden. Her father is the Prince of Saxe-Weiden, but his principality was lost late last year, when the people rebelled and tore down the palace. The whole family just barely escaped.”

“I remember the newspaper report,” Rhys murmured. “Is she not cousin to the Queen?”

“She is. I believe she is reading because the chairs to either side of her are unoccupied,” Natasha said. “It is a strategy I admire. There is nothing more awkward than sitting alone while the world ignores you.”

“As if that has ever happened to you,” Seth teased her.

“I never have found women to be agreeable company,” Natasha confessed. “Elisa is different…but I believe that is because she does not chatter about inanities, either.”

“Elisa was as rejected by society as that princess seems to be,” Seth said.

“The princess isn’t rejected at all, not like they once treated Elisa. But she does seem to have trouble getting along with people,” Natasha said kindly. “She has had a difficult time of it recently. She has lost her home, her country and now must live among strangers who don’t speak her language. Then there are all the silly rules and protocols. Being related to the Queen must not make her days any more comfortable. There are all sorts of expectations surrounding the royal family. Even distant cousins of that family.”

Rhys studied the princess and his head tilted to read the spine of her book as she lifted it closer to her face. Then he sat upright. “I do believe that is Thomas Robert Malthus she is reading.”

“Malthus?” Seth repeated. “Isn’t he the one who said we will all die from starvation and disease?”

“I believe his theory is somewhat more complicated than the way you state it,” Natasha teased him.

“You’ve read it?” Seth asked.

“Rhys lent me his copy to read,” Natasha said. “It was not the most optimistic of books. There’s little wonder the biologists and scientists all refute him.”

Rhys got to his feet. “Please excuse me,” he said distantly, as if his thoughts were far away. He moved toward the princess and her lonely row of chairs.

Natasha watched him go and sighed. “I didn’t get to warn him about the princess’ sharp tongue.”

Seth shook his head. “He is most definitely your brother, Natasha dearest. He is going to speak with the most unavailable and unsuitable woman on the entire ship, without an introduction, simply because he likes what she is reading.”

* * * * *

Anna frowned and blinked until the words swam back into focus. She was tired and sore and her eyes were weaker than usual today, but if she put on her spectacles to read, her father and Uncle Rupert would never forgive her. It was bad enough that she was reading where many people could see her doing it, yet the alternative was just as unattractive. Sitting and gazing out upon the gray water of the Thames sparkling in the sunshine and watching the masts and yardarms of the ships across the way as they lifted up and down would send her to sleep—a social faux pas of the worst kind.

So she read. Her copy of An Essay on the Principle of Population fit neatly into the pocket of her dress, which made it impossible for either her father or her uncle to spot the offending item. They were now both ensconced at the front end of the boat—ship—drinking and smoking cigars. She had been unable to prevent them from joining the rest of the men onboard, but tonight she would make sure her door was locked and bolted, right after she had checked on her mother and locked that door. Thankfully, the sun was not strong today, which would reduce her father’s pain, later.

“I know it is unforgiveable to interrupt while one is reading,” came the interruption, “but you do not look like you are enjoying Reverend Malthus’ prose enough to object.”

Anna looked up, blinking so her eyes would adjust. The man was standing a good pace away from her, which meant she could properly see him. It was only objects too close to her nose that obstinately refused to be seen clearly. “Does anyone actually enjoy Robert Malthus’ theories?” she asked curiously. “They’re quite depressing, if you read them with an expectation greater than entertainment in mind.”

The man was tall and seemed to be lean underneath his cutaway, but there was a breadth to the shoulders that removed any impression of weakness or fragility. However, his face was drawn, the cheeks high and sharp. The dark eyes above were looking at her directly, with frank curiosity. It seemed he was unaware of who she was, or he would not be so bold. Most of the people she had met in England were deferential to the point of obsequiousness.

He gave a small shrug. “I find his theories comforting. Knowing that the future is quite as bleak as he forecasts means that we as a society have time to address the issues before it is too late.”

Anna almost laughed. “You believe Malthus?”

“You do not?” He seemed puzzled. “Why do you read his essay if you have no faith in his theory? Perhaps you are reading for entertainment, after all.”

Anna felt her jaw loosen in surprise and she pressed her lips together quickly. “Who are you?” she demanded. “We have not been introduced.”

He straightened and faced her squarely, then bent his head. “Rhys Davies, esquire, at your service, Your Royal Highness.”

A common man. Her father would do more than strip the nightgown from her back if she were found dallying with a commoner. “I bid you good day, Mr. Davies,” she said as coolly as she could.

“I only ask about your motives for reading Malthus,” he replied, as if she had not dismissed him at all, “because I imagine his thoughts about the collapse of societies through overpopulation to be a comfort to you, given your family’s recent tragedy.”

This time Anna’s lips actually parted. She stared at the man. “Why on earth would one consider that to be a comfort?” she asked, the question rising to her lips despite her determination to be rid of him.

Mr. Rhys Davies gave another nonchalant shrug. “The subject matter of your book indicates you are a forward-thinker. I am quite sure you have questioned, even if only in the privacy of your own mind, why your father lost his principality and if it was through any fault of leadership.”

In fact, Anna had asked herself precisely those questions, in the dark hours of the night while listening to the clap of foreign-sounding Hansom cabriolets on cobblestone streets and the mournful fog horns that drifted all the way to Grosvenor Square on damp nights so unlike Saxony’s clear, crisp air. She found it irritating that this man, this commoner, seemed to know what was in her mind so precisely.

She snapped her book shut. “You are far too presumptuous for a man of your stat

ion,” she snapped.

“I sought only to distract you from reading that seemed disagreeable to you.”

“I did not ask for your service,” she said coldly. “‘Where we are there are daggers in men’s smiles’.”

He laughed. “Frailty, thy name is Princess.” He bowed from the waist, as she had seen the actors playing Hamlet do for their prince.

“That’s not the quote,” she said crossly.

“My apologies, Your Highness. ‘They have been at a great feast of languages and stolen the scraps’.”

She drew in another surprised breath. That was from Love’s Labour’s Lost, her very favorite of Shakespeare’s plays. “It is men like you who will be the death of us all,” she breathed and lifted the book up from her lap.

“Most likely,” Rhys Davies agreed. “That is a future which neither you nor I will live to see and there’s many a slip ‘twixt the cup and the lip. I am yet to understand why you persist in reading Malthus if he is so disagreeable to you.”

“That really is none of your business, Mr. Davies. Must I call for my father to be rid of you?”

He inclined his head in the short bow the English seemed to prefer. “I apologize for the shortcomings of my company, Your Highness. I hope the rest of your day is more pleasant.”

He turned on his heel and walked back across the deck to where the Lady Natasha sat with her husband in attendance. Mr. Rhys Davies clapped the Earl on the back and leaned over Lady Natasha and said something to her that made her laugh, her face filled with genuine pleasure.

For a moment, Anna roiled with envy at their naturalness, their enjoyment of life and their ease with each other and the people around them.

Were they talking about her? Laughing at her? She clenched her fist, hidden in the folds of her skirt. They didn’t know her. They couldn’t possibly understand.

So tell them, she thought. Explain it to that odious man, in a way he would understand.

“‘Truth will out,’” she whispered.

Chapter Three

After being properly snubbed by the Princess Annalies, Rhys remained by Natasha’s side for the rest of the afternoon. His enthusiasm for the search for a suitable wife had plummeted from a grudging reluctance all the way to the bottom of the Thames and besides, Seth was always good company. Every few minutes, another guest would come over to wish Natasha a happy birthday and give her a gift which meant Rhys did not have to circle the deck and mingle, as he should.

The Princess departed long before the cake was produced and the guests gathered around to see it cut. Two tall gentlemen, a stocky one with a tremendous silver gray beard, the other clean-shaven, but with a very square jaw, stopped and spoke to her. She merely nodded her head, rose to her feet and accompanied them from the ship, her skirt swaying gently.

Rhys watched the woman leave from the corner of his eye, while a duke whose name he missed in the fast flow of conversation told Natasha a hunting success story that was at least as old as the duke and wasn’t his achievement in the first place, but that of a hunt master in eastern England. Rhys had heard the story at least three times over the winter at various estates. Nevertheless, Natasha listened with bated breath and nodded and praised as if this was the very first time she had heard of it.

He impatiently dismissed from his thoughts any speculation about the Princess. She was argumentative and destined to become a spinster far too interested in books rather than babies.

Except that she was the daughter of a prince. No matter what her inclination, her family would find her a duke or prince and marry her off to stabilize the landless royals.

Either way, it was of little concern to him.

Why did she read Malthus, if she didn’t like what the author said?

* * * * *

At sunset, when the cold air turned damp, Rhys kissed Natasha on the cheek, shook Seth’s hand and left the ship along with most of the other guests. The chatter among them as they moved along the quay toward the long line of waiting carriages was positive. The party had been a marvelous success, another nod of approval for his sister and her husband.

He decided to walk home rather than try to find a cab amongst all the carriages. It was only a few miles to his rooms on Duke Street and most of that stretch was through St. James’ Park, skirting the lake.

As he walked, he enjoyed the early evening air. This had been an odd day where he had spent more time outdoors than he had for weeks before that. His work, which was absorbing and challenging, meant that he was not often away from his high desk.

The streets behind St. James’ Palace were busy with strollers heading for the park, or returning from it. There were a number of beggars camped upon doorsteps with their hands or their hats held up in appeal. Rhys dug a few coins out of his waistcoat pocket and dispensed them where he could.

The sight of the poor men and women in their rags, with dirty faces and missing and blackened teeth made him think once more about his conversation with the Princess and her opinion of Malthus. Normally, Rhys was a good judge of character and that was why the senior partners liked him to deal with clients. He could easily grasp what a client was not saying and it was often that hidden fact that unraveled an entire legal conundrum. With the Princess, though, he was at a loss. He simply didn’t understand her and the puzzle vexed him.

He turned the matter over in his mind as he walked home along the side streets. It was natural not to understand a woman like her. She came from a completely different world from the one he knew and understood. It was only her reading of Malthus that made him think they had something in common. He had made mistaken assumptions about her, that was all.

Even so, it bothered him that he had misread someone like that. It did not bode well for his work if he could make such a basic error in judgment.

The night was thick and dark by the time he reached Duke Street. The lamplighters hadn’t reached the street yet. Candles and lanterns from within the houses along the street were the only source of illumination, shining out through chinks in drapes, or fragile lace panels.

There were many more people walking along the footpath, heading for home after a day of work. His rooms were not the only ones to be found here and he knew many of the clerks from the Temple and the courts who lived here, too. He raised his hat to some as he passed, exchanging greetings.

The man who cannoned into him as he passed by did not raise his hat. He didn’t apologize, either, even though Rhys was thrown violently sideways and staggered almost into the gutter. The man gave a gruff “wotch it, guv,” as he passed, his chin tucked inside the high collar of a heavy coat, dotted with dew over the shoulders. He wore a battered bowler that disguised his face, leaving Rhys with the impression of pale skin and a sharply defined jaw.

Rhys brushed himself off, picked up his hat and crossed the street to his house and unlocked the door. His rooms were on the top floor and consequently were very warm in winter, for the warm air from the room heaters lingered under the roof. He had been quite happy living here for the last ten years, but if he were to marry, that situation would have to change.

It was another bleak aspect to the sudden turn in his life.

He closed the door on his sitting room and began to empty his pockets of the coins and detritus that one accumulated over the course of a day of going about business. He had developed habits from living and working in London that made his private hours more amenable, including emptying his pockets each evening before hanging up his jacket and removing his tie and collar and cuffs and rolling up his sleeves so he could relax.

He came across the folded stub of paper in his outer pocket and pulled it out and looked at it, puzzled at how he had come by the sheet. It was covered in typescript. He unfolded it and saw that it was a page from a book. Someone had callously torn the page out in order to acquire a sheet upon which to scribble a note.

It wasn’t a note. There was a line of text circled with heavy lead.

I think it will be found that expe

rience, the true source and foundation of all knowledge, invariably confirms its truth.

His heart squeezed. He looked up at the top of the page, where the author’s name appeared.

Thomas Robert Malthus.

Rhys realized he was sitting in the armchair, staring at the page while his heart thundered and his thoughts careened off each other like billiard balls.

The man who had rammed into him…the coat had been heavy enough, the hat low enough. It was possible the man could have been a woman. He recalled the impression he had receive of pale flesh and a keen jaw. That would fit. A tall woman might be able to get away with such a deception.

Again, his heart squeezed as he realized what a truly magnificent masquerade it had been. Even the gruff insult, spoken in a worker’s vernacular, had been precisely right. Rhys had thought nothing more of the matter beyond the rudeness of the man.

Was this the experience she sought in order to learn the truth? Was that the reason she read Malthus and could quote Shakespeare with such studied authority?

Rhys was still turning the page over and over, his mind busy, when his landlady arrived with his dinner, forcing him to let go of the delicious mystery and contemplate his suddenly ordinary, everyday life instead.

* * * * *

Anna was still becoming accustomed to the English practice of being “at home.” In Saxony, they had not called upon anyone. If people wished to speak to them, they asked for an appointment and if granted one, they would be expected to appear at the palace at the precise time and date and wait for their requested audience to be granted.

If, on the other hand, her father or mother had cause to speak to someone in the principality, the subject was sent a message by one of their secretaries, demanding their presence at the palace immediately. It was rare that the summons was not answered within the hour.

Heart Strike

Heart Strike Degree of Solitude

Degree of Solitude Kiss Across Blades

Kiss Across Blades Rules of Engagement

Rules of Engagement Marriage of Lies

Marriage of Lies More Time Kissed Moments

More Time Kissed Moments Hunting The Kobra

Hunting The Kobra Black Heart

Black Heart Eva's Last Dance

Eva's Last Dance Solstice Surrender

Solstice Surrender Inconvenient Lover

Inconvenient Lover Lucifer's Lover

Lucifer's Lover Wait (Beloved Bloody Time)

Wait (Beloved Bloody Time) Diana by the Moon

Diana by the Moon Delly's Last Night (Go Get 'Em Women)

Delly's Last Night (Go Get 'Em Women) Heart of Vengeance

Heart of Vengeance Law of Attraction

Law of Attraction Southampton Swindle

Southampton Swindle Chronicles of the Lost Years (The Sherlock Holmes Series)

Chronicles of the Lost Years (The Sherlock Holmes Series) V-Day

V-Day Kiss Across Time (Kiss Across Time Series)

Kiss Across Time (Kiss Across Time Series) Vale: A Short Erotic Vampire Romance Story

Vale: A Short Erotic Vampire Romance Story Dead Again: A Romantic Thriller

Dead Again: A Romantic Thriller Dangerous Beauty

Dangerous Beauty Blood Knot

Blood Knot Vivian's Return

Vivian's Return Veil of Honor

Veil of Honor Perilous Princess: A Sexy Historical Romance

Perilous Princess: A Sexy Historical Romance Dead Double

Dead Double Broken Promise

Broken Promise Royal Talisman

Royal Talisman